|

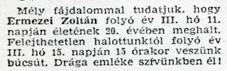

This is the first thesis in the writing Sentences on Conceptual Art by Sol LeWitt, 1967: “Conceptual Artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach”. This sentence occurred to me mainly because it may seem to be quite simple at first that the train of thoughts developed by several generations of artists finally made a newer generation declare the self-elimination, the end of arts. Yet, the situation emerging immediately in the “void” created after the end of arts is unendurable in several respects. It is unendurable for the person who believes that after having declared the end of something, he can still give this something further thoughts. Thinking fails here, it is drawn by a whirlpool, as tautologies like art=art cannot be given further thoughts. Of course, it is possible to understand them, and this kind of understanding is quite similar to introspection: undergoing an experience in a concentrated way. This experience can be a historic experience, too. Ad Reinhardt, whom conceptual artists looked upon as their predecessor, required of the artists to know the entire history of arts, and finally he condensed all the knowledge he acquired in almost totally black paintings. Still, he painted, he had not given up this traditional genre, he belonged to a former generation. A subsequent generation, which came to abandoning the task of producing works of art, had to condense all their experiences in something that is not an object in the ensuing situation. Perhaps they had to experience the experience in a very clear, concentrated – mystic – way, just to carry on tautologies. Emphasis was laid on going through, introspecting and experiencing, and on creating places where these vital processes could be concentrated, could be formed in a sense, and thus every moment in life became significant or acquired new meaning. In the March of 1975 Zoltán Érmezei had an announcement published in one of the issues of the daily newspaper Magyar Nemzet: “We regret to announce that Zoltan Érmezei, aged 20, died on the 11th of March this year. We shall pay the last honours to our unforgettable deceased at 3 p.m. on 15 March. We shall treasure his dear memory.” Perhaps nobody noticed this announcement in the newspaper at the time. Or those who did but did not know Érmezei, paid no attention, they could not have realized that it was an artistic gesture, symbolic self-elimination from a young man, who had decided to become an artist, and as he was absorbed in the ideas about the end of arts at the time, he reached the final conclusion. “Even at the very beginning, I thought in odd paradoxes about beginning and end,” says Érmezei. “I thought that everything begins at its end, and one cannot know where it ends. Even before I had done anything, I had the idea of a life-work exhibition in my mind. I handled these things as an oeuvre.” It is hard to define what “these things” really are. They are not works of art, because art has eliminated itself and has given up the production of objects. They are mainly experiences, concentrated moments, which are almost condensed to objects to such an extent that the person experiencing them has the illusion that it is possible to compose them. It is because the moment is so complete that the urge to record emerges immediately. This is why the origins of arts are often mentioned in this situation, which is called Post-Art by Érmezei. It is done in an indirect way by the means of documents that try to determine “these things”. The seizable quality, the independent existence of these documents can always be questioned – their position is like that of the lines drawn in the sand, which will be blown by the wind, and only the place where the event occurred will be remembered at best; an anecdote of the event may subsist and very often it is extremely difficult to tell the exact date. Zoltan Érmezei lived in this period of “post-art” for ten years. Photos, audio-recordings, strange documentary accounts and memos, notices, like the fragments of a diary, were preserved. Subsequent deciphering is difficult due to the ragged nature of recollection. Around 1978 he wanted to study stage design. Ilona Keserű recommended Gyula Pauer to him, who Érmezei worked with in Kaposvár later. Staying together continued in Nagyatád, where Pauer made his statue of Maya, an illusory female figure. In the subsequent period Pseudo-performances, called the theatre of reality, were organized around her. Pauer’s studio flat was the primary scene, and occasionally cultural centres housed the event. Érmezei took part in these events just as well as in the spontaneous music sessions at Peter Legéndy’s place. “Process documentation”, “artistic events” were the central ideas of this circle. “The essence of the whole thing was a continuous existence in art. One would regard his whole existence as art, experienced it as such. We were so much absorbed in this thought that there was nothing else for us. Life became art at the same time. It is a conjunction when you experience art as reality.” The paradox of this approach is, Érmezei felt it, too, that the necessity of the artistic medium somehow emerges in the meantime. “Because this is the excuse for the thing in the same way as Hajas’s excuse was that he remained within the borders of art though he entered into realms beyond art.” Thus one had to balance on a tightrope between the self-elimination of art, total disappearance and anonymity on the one hand and manifestation at an exhibition on the other. The rope is stretched tight between this two distinctly separated fundamental positions, yet it becomes unstable constantly by the act of putting the sign of equality between the two fields separated by it: between the process of life and the presentation of intensified moments, which nevertheless take form in the meantime. The rope falls onto the ground, winds like a snake on the no-man’s-field without an end to it. The only solution that can be found is concealment. Érmezei had his first exhibition, which was not known to anybody, in a factory in Csepel, where he worked for one year regarding his job as an artistic programme. He tape-recorded, made “music” of the sounds of the factory, and before leaving his office for good, where he had made advertisements, he left an environment behind, which was not realized by arranging the objects there, but by designating them as works of art. “The garbage belonged to the exhibition. It was not garbage, it was an exhibit. Perhaps nobody noticed it.” He held a “Post-Art Project” performance in Sodrás Street, where he lived together with Miklós Erdély, Pauer and Legéndy. His original plan was to have himself locked up in a room for a week or longer. “The exhibition would have been opened when I had been locked in.” The objective was to realize a continuous creative period with continuous documentation of being locked in. By this means time and space would have become reality, would have been experienced. In the end the performance was carried out like life, itself without any special notification, though a poster was made. It was then and there, in Sodrás Street that Miklós Erdély formulated the Theses of Marly, and Érmezei made a “place”, a strange, unsteady pulpit in order to remark upon the thesis that “a work of art is a place for what has-not-been-realized-yet”. Erdély presented the thesis here and took a photo of the “place” with him to Marly. Following this period of vanishing, when Érmezei worked together with several artists (Sándor Altorjai, Gyula Pauer, János Megyik), when he regarded his role as an “assistant” to be the realization of his post-artistic ideas; when absorption in thinking together with others, the euphoria of living in art meant entirety; when art meant everything; following this, or in the meantime, the period of becoming individual, breaking away, separating gradually began and thus the urge to create works of art was gently formulated. P.É.R.Y. Puci meant the first step. This is a fictitious artist who was embodied by Pauer, Érmezei and Rauschenberger, whose plein-air pictures of the borderland were shown at an exhibition in Pécs in 1987. The second step was taken when he and Rauschenberger made clay impressions of themselves, as if the distortions in the cast were produced by the attempt to get out of living in art only, by the anguish of taking form. Though the human figure appears and becomes visible in the artful space of reflections, transparencies and projections in their collective mirror-labyrinth-painting, its place is completely uncertain, and it is almost impossible to denominate the spatial relations. The tongue fails. The third step is being taken now, when Érmezei presents this exhibition. Budapest, 13-14. september 1990. Translated by Katalin Varga |

|

* Published in: Corpusok • Feltárás. Érmezei Zoltán és Rauschenberger János kiállítása / Crucifixes • Revelation. Exhibition of Zoltán Érmezei and János Rauschenberger. Exh. Cat. Budapest Galéria Kiállítóháza, Lajos. u., Budapest, 12.12.1990–20.01.1991. s. p. |

|

Érmezei in the 1th Pseudo-Performance of Gyula Pauer, Nagyatád, 1978 (Photo: Gábor Dobos) |

|

Érmezei in the Sodrás Street, Budapest, 1979 (Photo: Pauer Archive) |

|

Érmezei in the 3rd Pseudo-Performance of Gyula Pauer, HNG, Budapest, 1979 (Photo: Gábor Dobos) |

|

Érmezei as assistant of Gyula Pauer in his performance Metamorphosis, Budapest, 1981 (Photo: Tamás Kende) |

|

Érmezei and Bea Pászty at the opening of the exhibition of P.É.R.Y Puci, Pécs, 1987. (Photo: Péry Puci) |

|

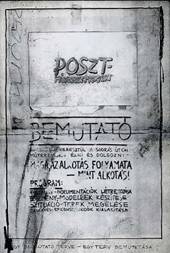

Zoltán Érmezei: Documents of the Post-Art Project, 1979, xerox-copies, Artpool Researche Center, Budapest (click on the pictures to enlarge) |

|

Zoltán Érmezei: Poem for Gyula Pauer, c. 1979, Bequest of Miklós Erdély (click on the picture to enlarge) |